Sicilian Sunday bake-off

Never argue with a Sicilian when cakes are on the line... Not only is Sicily one of my favourite places in the world, but they also have perhaps the best patisserie.

Having been roped into an office bake-off, I couldn't resist dipping into Sweet Sicily for these almond biscuits. My husband tells me they're very very sweet - 30% sugar, in fact.

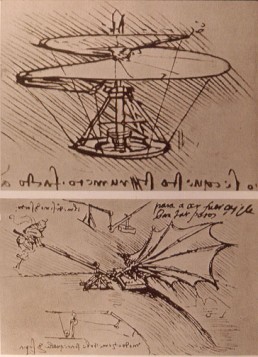

The ornithopter that really flies...

One of mankind's great dreams is to fly like a bird, and ornithopters have been a staple of fantastical fiction since Leonardo di Vinci drew his first speculative designs. But did you know that planes that flap their wings are a real technology? In 2010, what appears to be the world's first successful human-powered ornithopter sustained altitude and airspeed for an incredible 19.3 seconds.

Apparently ornithopters have some advantages over fixed-wing planes. They're more energy efficient, maneuverable, can use shorter runways and even perch on difficult terrain.

So watch this space - a flying machine like the one below might be coming to an airport near you sooner than you think.

Who says you can't establish your own country?

Calling all future seasteaders. A wonderful article in the Independent by the first journalist to stay overnight on the Independent Principality of Sealand - a Second World War anti-aircraft fortress off the UK coast that's been an unofficial micro-nation since the 1960s.

Seven miles off the coast of Suffolk, there is a country. It isn't a very big country. In fact, its surface area extends to no more than 6,000 square feet, which is about twice the size of a tennis court. You won't find it on Google Maps and it isn't a member of Nato or, indeed, the EU. But it exists. And I know, because I've been there...

The feature was published in 2013, but it was a joy to discover - even two years after publication. What's really cool is that Sealand has its own passport, coinage and the Bates family have occasionally got into gun battles defending the place. The micro-state has even embarked on international diplomacy - they kidnapped a lawyer in 1978, and the German government had to sue for his release. Brilliant stuff and a fascinating read for future seasteaders.

Reading the Rocket: Best Novel

Are there any recent SF novels as good as The Three-Body Problem? Novels with world-changing ideas? Wild sweeps of imagination? Nail-clenching consequences for the characters? The ability to inspire my younger self to a passion for science? Published post-2010 and in the English language...

Going by the rest of the Hugo nominees for Best Novel, the answer would be... erm, no.

I didn't read all the novel nominees cover-to-cover. There were several reasons for this. I had a health scare and I'm writing my own novel at hell-neck pace. I ended up skim-reading the first three chapters on a bus yesterday afternoon - hours before the voting deadline. I expected this to be a problem, but it wasn't. Mostly, it saved me several hours of my life.

#1 The Three-Body Problem by Cixin Liu (translation by Ken Liu)

This book is incredible. Period.

It begins with a professor tortured and executed for lecturing revolutionary science, while his daughter watches. Then she, too, is threatened for the seditious act of reading Rachel Carson's Silent Spring. Soon we're facing the critical dilemma of the book - why are a group of physicists committing suicide? And why do they believe physics does not exist?

The writing style is mind-blowing. It's sharp, crisp and fast-paced, but without losing the sense of place or characterisation. The ideas are huge, e.g. what is the laws of physics changed in time-and-space? But conveyed light touch, without info dumping.

I haven't finished The Three-Body Problem, but I've carried on reading it. My husband, who also bought a supporting membership, is avidly reading it. This is a book I wish I could write, but don't have the ability, which is - after all - the purpose of the Hugo Awards.

This is a book that would have inspired my teenage self to a passion for science. It's a book that expresses the wonders of the universe, the marvels of human potential, and all our frailties and our triumphs. This is on par with the Foundation Series or Rendezvous with Rama. This is downright good. I hope it wins the Hugo for best novel because, otherwise, something is wrong with the world.

#2 Skin Game by Jim Butcher

There's no doubt that Jim Butcher is among the best pulp writers working today. I hadn't encountered his Dresden Files before the Hugo Award nominees were announced, but I've now read all fifteen of them, including the latest Skin Game...

Reading all fifteen Dresden Files was an onerous task (NOT), which I mainly completed on holiday in Sicily. They're great urban fantasy about a wizard in modern-day Chicago who fights off faerie, vampires, the undead - all the usual suspects. There's nothing especially original about The Dresden Files, but they're sharp, witty, modern and the quality doesn't flag over fifteen books - an achievement in itself.

Moreover, they tackle some heavy-duty ethical dilemmas. Should you sell your soul to the devil to save your friends? Is evil about actions or intentions? Do evil powers always lead to evil acts, even if your intentions are good? Should people who've committed heinous acts be given a second chance?

I've added Blood Rites (#6) to my list of 'How to Write' primers. These are very very good books. On par with noir greats like Raymond Chandler, and that's high praise coming from me.

#3 No Award

Sorry, some things have to be done...

#4 The Goblin Emperor by Katherine Addison

Once upon a time, there was a book about a young man (or ferret or space alien) who unexpectedly found he had become Emperor. So he went to a pseudo-medieval court in which everyone had silly names like Unseelieboudie or Aehterlieasii. And there he sat around on his throne while court machinations happened and no one liked him, but they had to bow and scrape. And probably - somewhere beyond the bit I read - someone tried to kill him...

You probably read this book, aged about seventeen. I did, about a thousand times. I read Daughter of the Empire, which is actually good. I also read... well, a bunch of stuff by David Eddings, and a bunch of rubbish stuff I've forgotten.

This book reads exactly like the rubbish stuff I've forgotten, but without any of the drama, conflict or over-described silly costumes. It does have racism and child abuse (apparently, I didn't notice in Chapters One through Three), which may explain why it was on the Hugo Award nominee shortlist. Let's put it this way - The Goblin Emperor wasn't there for its originality...

It's very talky, but it's that talky that happens in bad fantasy novels where Lord Chancellor Xapenasis the 15th needs to talk about the religious rites of Sabenaisis that the new king Yerobozerbilos XIII must perform to placate the powerful Sreyaueona family before his coronation. The experience is akin to listening to the US President discussing Chicago onion futures, if you were a Martian native who didn't eat onions.

i don't think I would have no-awarded The Goblin Emperor, but I read it within minutes of the first three chapters of The Three-Body Problem and they simply don't belong on the same shortlist...

#5 Ancillary Sword by Ann Leckie

I have an admission to make. I tried reading Ancillary Justice last year, got a chapter in, and gave up. I felt I should read it, as it was getting a lot of hype, so I tried again... got two chapters in and gave up.

I have an admission to make. I tried reading Ancillary Justice last year, got a chapter in, and gave up. I felt I should read it, as it was getting a lot of hype, so I tried again... got two chapters in and gave up.

My major problem with Ancilllary Justice was the dry, flat and emotionless first-person narrator, which I attributed to a brilliant, but misguided, attempt to write in the voice of a former AI. Ancillary Justice is the only book I've read to make an (apparently) dead body on page one sound deathly dull.

The Hugo packet excerpt of Ancillary Sword exceeded Ancillary Justice in its dullness, by containing zero ideas, zero (interesting) conflict and zero (meaningful) drama. Reading the excerpt on the bus, the main conflict in Chapter One involved two terribly-polite middle-class people who were unsure whether to take rose-glass teabowls on a spacefaring warship. One of those middle-class people was supposed to be a former AI who had lived in thousands of bodies. I promise... it was less fun to read than it sounds.

Later, the former AI agonises over whether another character - whose only distinguishing trait is lilac eyes - is too anxious and green to take along. It turns out the AI's boss has done some cruel and unusual surgery to lilac eyes in order to spy on the mission. Again, I'm making this sound interesting. It wasn't. And it wasn't obvious it was taking place on a starship either. It could have taken place in a Japanese tearoom. Or a freelance hot-desking facility in contemporary San Francisco. Or at a dinner party of accountants in Fulham, London.

All the characters were uniformly polite, middle-class, and had exactly the same voice... Oh, and had brown skin and brown hair and brown uniforms... It was like reading a weird clone mission. Maybe they were clones. Maybe the author had some strange belief that an AI wouldn't notice that human beings look different, which would be weird if they'd been working with them. Heck, I think cocker spaniels look different and they're so inbred that mine has the same great-grandfather twice.

And the brown skin? Have you met anyone who says 'I have brown skin'? People don't have brown skin. They have milk-chocolate skin with blue-black hair. They have caramel skin. They have coffee skin. They have fair skin with freckles. They have olive skin, and honey-gold skin, and pale skin bronzed by the first touch of summer. They have midnight-dark skin, deeply furrowed from working outdoors in the sun. Never brown skin...

So, yep. Limited conflict. Insipid meek ideas. Boring dialogue. Boring, poorly-described characters. No real sense of the lived experience of being an AI who'd been in lots of bodies. Silly made-up names like Tisarwat (I checked, not a real name), which fit the bad fantasy trope of 'sounds a bit Asian to ignorant Westerners', but could be replaced by 'Sam' for all the difference it makes.

Yuck... Yuck... Yuck...

Simply insipid. And massively over-hyped.

#6 The Dark Between The Stars by Kevin J Anderson

I find Kevin J Anderson's books boring. He spends too much time telling, and not showing, which means I don't care about his characters. Also, the density of original ideas and original situations is low. The Dark Between The Stars was no exception. It didn't annoy me. I was simply bored and insta-forgot what I'd just read.

Aggressively mediocre.

An Open Letter to Tom Kratman - Big Boys Don't Cry

Dear Tom,

Yesterday I read your Big Boys Don't Cry, which is nominated for the 2015 Hugo Award for Best Novella. There were bits of Big Boys Don't Cry that I enjoyed, but your novella was a struggle to read. I nearly gave up at the 7% mark. It had basic problems with prose style and narrative technique, which a good writing group could sort out in five minutes.

I'm sure that doesn't bother your fanbase, who are interested in ideas-driven military SF written by a career military officer. And who understand the term 'echelon left' (page 87). But it will bother anyone who reads SF primarily for the characters and drama. And I understood why Big Boys Don't Cry was dismissed as dreck by some non-Puppies.

I'm not a great crit group, I'm not even a published (fiction) author, but the technical problems with this novella were so blindingly obvious I thought I could help. I've made this an open letter in the hope my writing advice may help others!

[This is not a political attack. The Water That Falls On You From Nowhere which won (WON?!!) the 2014 Hugo Award for Best Short Story is also on my crit list. There is no way The Water should have won a Hugo... It wouldn't have survived five minutes on my creative writing MFA without the red pens coming out].

The Good Stuff

(skip to 'the bad stuff' for the writing advice)

My work-in-progress novel has a living weapon protagonist, which is probably why I found this story more interesting than I would have otherwise. I enjoyed reading the traumatic memories of autonomous "Ratha" battle tank Magnolia, who learns in her dying moments how she has carried out out war crimes for her human masters. I loved that autonomous tank. Heck, it was a self-identifying female tank - what is there not to like? For example, Kindle ref. 405:

"Big Boy here won't cry". Two lies in a single sentence. I am not a boy. And I will cry.

I liked the brutal training process for teaching Magnolia military tactics (Chapter 8). The story flew at that point and I really got into it. I liked how the Rathas were trained by receiving pleasure every time they performed the 'correct' actions. The uber-logical AI with no emotions is an SF trope, but animals are primarily motivated to do what they enjoy. Future AIs will doubtless be like Magnolia - created to love what they do (even if it's cleaning loos).

Chapter 8 also had some moving bits. The tank was the most sympathetic character in the story (more on that in a mo) and your writing was affecting when she was hurt, such as Kindle ref. 781:

All alone in its sterile virtual world, a baby Ratha weeps in agony without comprehension, as the sun stands still over a fallen corpse that will not die.

The Bad Stuff

Hook ye' reader, varmints!

Chapter 2 of Big Boys Don't Cry begins (Kindle ref. 71)...

The valley ran northeast to southwest.

Well, I'm gripped... Don't know about you, but I'm dying to know what happens next. A valley runs northeast to southwest. Wow, valleys never do that... I must read on.

So what does happen on the next line?

There was a winding cut through the rough center, a dry riverbed, a wadi, which was filled occasionally by unpredictable rain.

As I read this, I thought 'is this a geology primer or a military SF novella about autonomous tanks'? Then I thought, 'Well, that explains why I'm bored by a story about autonomous tanks.'

So technical lesson one... How to open a chapter.

Brighton Rock by Graham Greene has possibly the best opening line in literature:

Hale knew, before he had been in Brighton three hours, that they meant to murder him

Who is Hale? Why do they mean to murder him? And why in the sleeping seaside resort of Brighton, of all places? Jim Butcher, author of Hugo-nominated Skin Game, is also a master at hooking the reader. Turning to a random chapter in Blood Rites, the first line of Chapter 3 begins:

Thomas's senses evidently didn't compete with mine, because the Black Court vampire was up to its shoulders in the Beetle before he choked out a startled, 'Holy crap!'

Yep, that's a drama-filled opening alright. We're hurled headlong into the action, the intrigue, the murder... Will Thomas survive? Will he beat off the Black Court vampire? Or is that the end of Harry Dresden's half-demon brother...? Find out in paragraph 2...

Big Boys Don't Cry, Chapter 2, has a drama-filled opening too. Unfortunately, it's buried five paragraphs down on Kindle ref. 71.

Magnolia never heard the death scream of the lead unit, Leo.

THAT is your line one. A competent editor, or your friendly local writing group, would have put a huge circle around this line and a big arrow pointing to the beginning of your story.

Let's experiment. Let's take this line, and the description (also on Kindle ref. 71) of how Leo blows up, and rustle up a better opening line. How about:

Magnolia never heard the death scream of the lead unit, Leo. He simply disintegrated, his main turret flying end over end.

NOW we're talking. Why did Magnolia never hear the death scream of Leo? How did a Ratha battle tank simply disintegrate? They're being ambushed! By an enemy even more bad-ass than a battle tank! Aggghhh, I MUST... Read... on...

Show, don't tell

Let's stick to Kindle ref. 71 for the second technique problem - too much 'telling' and not enough 'showing'.

Imagine watching the movie Psycho with no visuals and a bored friend narrating the events."Well, she's about to be killed by a psycho with an butcher knife'. That's TELLING. Now imagine your friend says, "She's in the shower and there's a shadow growing on the curtain. It's a huge knife!". That's SHOWING.

'Telling' sucks tension and drama from the story because the reader doesn't experience events alongside the point-of-view character.

Now let's go to Kindle ref. 71 and I'll highlight in bold every 'tell':

"They missed the big threat, precisely because it wasn't very big. It normally took a lot to make a Ratha simply distintegrate. Fifty grams of anti-matter contained in a magnetic bottle was suddenly driven up into the underside of the vehicle then released from its magnetic bottle as the bottle's generating mechanism was destroyed. Thus explosively joined with the Ratha's lightly-armoured belly plate, it was enough to do the trick. Magnolia never heard the death scream of the lead unit, Leo, so rapid was his destruction. But the image of his main turret flying end on end, like some frying pan out at the hands of a titanic juggler**, was seared into her memory."

That's a LOT of telling. You're not SHOWING us what Magnolia sees and her interpretation of it, you're TELLING us what happened. In every sentence. You even tell us that the main turret flying end-to-end was 'seared into her memory'. You don't need to tell us that - really. If your writing is evocative enough, we can guess that on our own.

**You'll see I've italicised the 'frying pan out of the hands of a titanic juggler' metaphor. Frying pan? Seriously. You want readers to be thinking of frying pans and jugglers in the middle of a firefight. Hellfire and brimstone, maybe. But jugglers? JUGGLERS?

Now let's rewrite as real-time action to place the reader in the moment with Magnolia. This isn't great (or even good), it's not edited, and not going to get me a Hugo nomination, folks... But:

Magnolia never heard the death scream of the lead unit, Leo. He simply distintegrated, his main turret flying end over end, his four walls blasting in every direction...

...She stopped to replay her memories, zooming in on Leo in his last moments. A magnetic bottle of anti-matter had suddenly exploded from the ground and slammed into his lightly-armoured belly plate.

More drama, but the same information. Hope you agree.

Is this a cardboard villain I see before me?

Big Boys Don't Cry is an anti-war story about a tank with a conscience. She is manipulated by bad people. Very bad people. At least one reviewer said Big Boys Don't Cry had:

'meatsack villains so thoroughly stupid, corrupt and evil that they come across as cardboard black hats'.

Let's head over to Kindle ref. 620, where we find one such villain.

Magda Dunkelmeier, the new governor, was a modern woman, certain modern in her attitudes. She was certain - absolutely convinced - that only some sort of men's conspiracy had removed her from the center of moving and shaking. Either a conspiracy or perhaps the machinations of the little bimbo of a CD-seven who had not only caught the eye of the secretary but coverted Dunkelmeier's previous job.

Ms Dunkelmeier goes on to start a civil war and massacre some children...

The real world has good and bad people, corrupt and idealistic people. It sometimes has people who are destructively idealistic - the Knight Templar whose fervour for righteousness swings them to evil. Readers intuitively know this. The further you swing your imagined world from that balance, the less they're prepared to suspend disbelief in your story. In short, the more rabid you sound, the less persuasive you are.

Big Boys Don't Cry has, apart from Magnolia, no characters who behave other than like psychopaths (tell me if I'm wrong). In the real world, around 1% of people are clinical psychopaths. So your world is MASSIVELY unbalanced from reality.

Can we change that? Well, yes. First, clarify whose point-of-view we're in. Whose opinions are these about Magda Dunkelmeier?

- Magnolia? Would a tank really know or care this much about politics?

- Her political opponents? Her political allies presumably don't think this about her.

- The all-knowing author? In which case, you, Mr God-like author are a cruel God... Because you should know all your characters, even the most loathsome, have something heroic about them.

Let's take a fictional example. Macbeth by William Shakespeare. Macbeth's descent into murderous tyranny stems from positive characteristics - his martial valor, his love for his country, and his love for his wife. His remorse at seeing his friend Banquo's ghost doesn't stop him being a complete villain.

So find those positive traits in Magda Dunkelmeier. Ether tell us about them. Or make it downright clear that this is Magnolia's (negative) opinion of her. Then have her kill the kids. I promise you, your writing will be 4,000 times more interesting that way.

More wooden villainy

Good fiction has characters wrestling with moral dilemmas. Their choices - good or bad - move the story forward and keep readers turning the pages. Apart from Magnolia, I didn't notice (again, I may be wrong), characters struggling with difficult moral choices. They tended to deliver a few lines of exposition from Villain Central before vanishing again.

Take this mansplaining by a superior to a female technician about the crying Ratha AI (Kindle ref. 781):

He laughs, "Nonsense. You're anthropomorphising. These things don't cry. They can't. They're just machines. Besides, it has to learn to take it or we'll end up having to scrap the unit. It's a waste, of course, but it's cheaper to reject the brain and reuse the materials than to risk putting an unsuitable brain in a real Ratha Hull."

At the moment, he's a cardboard baddie providing some exposition to the reader. Now let's see if we can give him a dramatic moral choice, which reveals a character motivation. His emotional state - in this paragraph - is 'you silly little person, questioning me. I know these machines better than you.' So let's break up that long speech and see if we can build some dramatic tension. Something like:

He laughs, "Nonsense. You're anthropomorphising. These things don't cry."

The technician's emotional state is 'Poor little machine, but I've only just started this job and I don't want to look like a stupid noob" . So maybe we could force some more drama out the scene by making her persist and try to use a scientific example to convince him. Something like:

She gazed sideways at the screen, 'Are you sure? It's curled up like the sim rats in our animal tests'.

Then he might think 'hmmm, she's got a point, but she's still a noob with the IQ of a teapot and, anyhow, I can't entertain the possibility that this thing might feel because I'd never forgive myself. Also, I can't delay the project, not in this fictional universe where 75% of people are descended from Hannibal Lector. They'll be queuing up to execute me...' So he might say:

He stepped away from the console and shrugged. "I'm certain. It's not a rat, it's a Ratha. Completely synthetic." He frowned, thinking about Ms Dunkelmeier. "Besides, it doesn't matter if it feels. It has to learn to take it or we'll end up having to scrap the unit. And I'm not going to be responsible for explaining THAT to the committee."

Now he's still dismissing her, but has to question his actions and change his argument. Then he pauses a moment, uncertain about his ethical choices, but quickly self-justifies his behaviour with another sentence that reveals a (possible) character motivation. Now his conscience is clear. The little AI can go squeal all it likes. Hopefully, now the scene looks a little more 'real', behaviour-wise, a little more dramatic and less like an info dump.

Incidentally, I'm using a screenwriting technique called 'turning a scene' with 'beats'. It's where you script a conversation through moment-to-moment action/reaction, which brings an encounter to a turning point. A 'beat' is the smallest unit of action or dialogue. A 'turning point' is the moment where plot moves forward.

Here, the turning point is the man deciding to leave the little AI weeping. He's making a significant moral decision (the wrong one). Had he said 'Well, actually, you've got a point. It might be crying. Let's cut the poor little Ratha some slack and I'll speak to my boss', the plot would have turned out very different.

You can read more about 'beats' and 'turning points' here and here (see page 64). And here I've found an example of a scene deconstructed into beats and turning points. The definitive book is Robert McKee's Story.

And finally...

Apologies for this being rather long. It is sincere feedback.

Feel free to comment or email me.

Yours,

Vee

Reading the Rockets - Best Graphic Story

I'm currently reading and ranking the Hugo Award nominees for 2015 and I've moved onto ranking Best Graphic Story in ascending order (worst to best).

I'm not a regular reader of graphic novels and it's hard for me to review these titles on their own merits. I have the entire series of Transmetropolitan, Sandman, Sin City, Bone and Amulet. And I own Maus, Laika, Django Unchained and Persepolis - if that helps show what I'm judging against.

#6 Zombie Nation

Zombie Nation wasn't included in the story folder sent to voters, but - after a little Googling - I found the webcomic online. The nominated graphic story is called 'Book #2: Reduce Reuse Reanimate' and I couldn't find that, but I did have a look at some of the cartoons.

Zombie Nation wasn't included in the story folder sent to voters, but - after a little Googling - I found the webcomic online. The nominated graphic story is called 'Book #2: Reduce Reuse Reanimate' and I couldn't find that, but I did have a look at some of the cartoons.

I'm telling you this because I worry I missed something. Zombie Nation is supposed to be a "funny webcomic following zombie slackers during the zombie apocalypse", but it wasn't funny and I didn't see any slackers. I did see some cartoons of zombie celebrities with random captions.

Zombie Nation zoomed over my head. I couldn't even see why someone else might like it. Add to that my dislike of all things zombie, and that makes it a solid 'No Award' candidate.

#5 Sex Criminals Volume 1: One Weird Trick

Sex Criminals has the best story premise ever.

Couple can stop time by having sex. Couple use this ability to rob banks.

Unfortunately, the delivery and plotting doesn't match the premise. Or, in less technical language, I had no idea what was going on. Or where we were in time. Or whether we were robbing a bank now... or in the past...

Let me explain the plot. Or what I thought was the plot.

- We have a couple having sex. Okay, that makes sense.

- Then we go back in time to recount the heroine's history of sexual experimentation and how she discovered she could stop time by masturbating. I have no idea why we needed this backstory.

- Then, suddenly, we're robbing a bank, and being pursued by three people in white. One of whom is a woman in a cutaway coat and black panties. Okay...

- And then we're following the hero as he recounts his entire life history of visiting sex shops and viewing porn on the internet. Again, why? Humans have sex. Snails have sex. This doesn't need backstory.

- And then we have a long bit where the heroine and hero talk to each other... about sex. There is some singing. They decide to rob a bank. Hurrah. Something happens.

- Now we're back to black pantie woman. Is she the sex police? Is anything going to happen in Volume 1 of this graphic story? Apparently not.

- Sex cop pantie woman has children and a life where she is fully clothed. The hero and heroine talk about their sexual history again. I never knew sex could be so emotionally fraught and complicated until I read this graphic story. Obviously I'm doing it wrong.

Perhaps I wasn't the target audience for this graphic story. I expected sex with bank robbery. I got a couple reminiscing about their sexual history and emotional problems. Mainly in flashback. Without much happening.

The story could have been more clearly structured, perhaps? Maybe focused more on a couple visiting a sex therapist? So you didn't expect any bank robbery? Who knows... Perhaps Sex Criminals was simply too 'experimental' for the likes of me.

#4 No Award - self-explanatory. Anything below this is the pits. Or Sex Criminals

#3 Ms Marvel Volume 1: No Normal

My favourite writer's guide How NOT to Write a Novel has this to say about introducing your hero/heroine:

My favourite writer's guide How NOT to Write a Novel has this to say about introducing your hero/heroine:

If the first thing a character does is poo in front of the reader, the reader will think of him as the Pooing Character forevermore.

And that, in a nutshell, is why Ms Marvel is languishing at #3. Ms Marvel is a politically-aware comic, which wants to represent modern Western urban society. Ms Marvel wants to ensure that all superheroes are not WASP men who look freshly sauntered off the set of Triumph of the Will

Ms Marvel there has... drum roll... the Muslim Character. Now Kamala is a cute sassy likable young heroine who is destined for great things, but - unfortunately - we don't see that until halfway through Volume 1. We don't get a character introduction at all, not a proper one. Because on pages 1-10, she doesn't have a personality, flaws to overcome or a life goal. She is simply Muslim. Stereotypically, head-bangingly, crassly Muslim.

- Inclusion of the word 'infidel' (on page 1) - CHECK

- Inclusion of racial bullying against heroine by privileged white person - CHECK

- Inclusion of not drinking alcohol and food restrictions - CHECK

- Inclusion of excessively devout Muslim family member (#Snark Alert# - in a later volume he flees to Syria after blowing himself up in a shopping centre #End Snark#) - CHECK

- Inclusion of excessively strict parents, especially anti-Western repressive father - CHECK

- Explicit reference to hijab wearing - CHECK

Anything I've missed? Wearing a burka? Arranged marriages? Being kidnapped and taken to Pakistan to marry her cousin? I especially loved the 'Shalwar Kameez A.K.A. Pakistani clothing' footnote somewhere near the end of the story. Just to educate the (assumed) brain-dead reader from rural Alabama who wanders around New York thinking 'brown people.... weird... must be from Venus'.

Note to cartoonists. Assume your character is a person. You know, a person, like you. With hopes and desires and passions, who is brave and vulnerable, wonderful and flawed. Write that person. THEN make your world as it is for us Londoners - you know, where everyone isn't white, straight, a man or from Norfolk* *Norfolk A.K.A. county in the East of England, United Kingdom often the butt of incest/inbreeding/parochialism jokes.

Apart from that, it's a great comic. Well drawn, Kamala is sweet and funny. And her experiences are relatable to everyone who has ever been a teenager. I just wish that stuff happened on page 1-10 and her racial/cultural/religious heritage was drip fed as we went along. People aren't simply a checklist of social justice categories, after all.

#2 Rat Queens Volume 1: Sass and Sorcery

Rat Queens apparently improves dramatically after Volume 1, which is why I've ranked it #2 and not below Ms Marvel.

It's a feminist take on D&D featuring an adventuring party made up entirely of women. They drink, they brawl, they take drugs, they have sex, and some of them 'ain't no size 2'. Now someone in town is trying to kill them and they have to find out who.

I was impressed by character development in Rat Queens. It's not easy to create an ensemble cast who don't merge into 'leader plus friends', especially in visual format and in a first volume. Here you can tell by page one, simply by their stance, that these are very different people. It's not even clear as the story progresses who is the 'leader' (Hannah?) - they all get page time.

It's a promising start to the series and, apparently, as Rat Queens progresses, it delves into each character's backstory. Their problems, hidden secrets and conflicts. There was a clear plot (who is trying to kill us) from the get-go. And I was never confused about where I was, what was happening, or what was at stake.

On a less positive note, I found Rat Queens about as edgy as a tennis ball and I don't think Volume 1 is the best showcase for the series. There was slightly too much 'Women in fiction can drink too! And fight! And like sex! And have plump thighs! Woohoo, aren't I subversive?' Ok, ok, I get it. Have a gold star. Now let's move on with the story.

#1 Saga Volume 3

I was reading Saga before the Hugo nomination for Volume 3. I love this series and the strange future-fantasy world the author has created. Volume 3 isn't the best volume, but it's hard for me to judge as a standalone as I've read the others.

The series follows two former soldiers from long-warring alien races and their struggle to care for their daughter, Hazel, as they're chased by the authorities. Hazel is born at the beginning of Volume 1 and narrates part of the story as an adult.

Saga has lost narrative momentum as the series has progressed, but I've found it remains imaginative and entertaining. I don't think there's one baseline human here. In Volume 1 artist Fiona Staples even solved one of my longstanding character niggles - how do you dress a person with more than two legs? (Answer: a prom skirt)

There are flying tree spaceships. There are Egyptian lying cats. There are family feuds, blood feuds, assassins, deaths, births, love affairs, lots of running away. The standard palate of all-purpose human conflict that has driven good storytelling from time eternal. Big thumbs up from me.

Reading the Rockets - Best Short Story

If you're interested in reading science fiction, you'll know about the Sad/Rabid Puppies controversy that's dogged this year's Hugo Awards. The furore encouraged me to buy my first supporting membership, which gives me the right to vote for the prize winners. I'm currently reading my way through the nominees.

First up, Best Short Story. The nominees are:

- “On A Spiritual Plain”, Lou Antonelli (Sci Phi Journal #2, 11-2014)

- “The Parliament of Beasts and Birds”, John C. Wright (The Book of Feasts & Seasons, Castalia House)

- “A Single Samurai”, Steven Diamond (The Baen Big Book of Monsters, Baen Books)

- “Totaled”, Kary English (Galaxy’s Edge Magazine, 07-2014)

- “Turncoat”, Steve Rzasa (Riding the Red Horse, Castalia House)

These range between dire and good. And only one of them, in my view, is even remotely worthy of being considered for a Hugo Award (if I'm being charitable). And that, surprisingly, is the military SF story Turncoat.

First, a disclaimer. I don't blame the low quality of this year's nominees on the Sad/Rapid Puppies. Last year's winner, The Water That Falls on You From Nowhere, also had basic flaws in style and plot.

So why are the award nominees so poor? I think Eric Flint had it nailed when he wrote:

The truth is, there is no financial incentive at all for a modern F&SF author to write anything except series and multi-volume stories. For the good and simple reason long ago enunciated by the bank robber Willie Sutton: “That’s where the money is.”

There is no incentive to write professional-quality short fiction if no one will pay properly for it. Any writer who thinks they can get paid for writing a novel (or multi-series), will do. The only reason to write F&SF short stories is to practice your craft and/or raise your profile among other writers. Neither of these motivations is likely to consistently generate high-quality storytelling.

Now onto the Hugo Award nominees..

#6 The Parliament of Birds and Beasts by John C. Wright

I've read several of John C. Wright's stories. I've even bought his City Beyond Time. The Parliament of Birds and Beasts isn't his best work. My husband was more charitable than I, but my impression was FAR too much dialogue and nothing much happening.

The Parliament of Birds and Beasts reminded me of the Chronicles of Narnia, but with all the interesting action-adventure removed. Many animals stand around discussing the disappearance of man from a glorious mythical city. Then some Angels appear and the animals rise up to replace mankind. THE END.

The imagery is beautiful in places, e.g. 'in the center of the citadel rose a tower tall and topless, its dome open to the sky like an ever upward-peering eye'. Unfortunately, having little exposure to the Christian faith, the story was lost on me. That made it a 'No Award' candidate.

Storytelling is a human universal. We can still appreciate The Illiad today, and it's three thousand years old. If I need a Bible primer (or any other primer) to understand your story, it's not eligible for a Hugo Award.

#5 Totaled by Kary English

Maybe I'm spoiled. Maybe I'm jaded. Maybe I belong to some badass writing groups, but I routinely see stories of similar quality and on a similar theme to Totaled. It's competently written, it's perfectly decent, but the 'research subject is decanted from their body and ends up losing their mind' story is as old as Flowers for Algernon.

Also, on a technical point, the narrator spends too much time in her own head (literally). If I'd seen a story like this at my crit groups, I'd have recommended the author hack a few of the early paragraphs and cut straight to the interaction with the protagonist's colleague, Randy Moreno.

A fun read, but ultimately forgettable. Sorry.

#4 On A Spiritual Plain by Lou Antonelli

With On A Spiritual Plain we move from actively 'meh' to 'good, but flawed'. This is a story about a chaplain on a mining world where some hokum magnetic fields mean that the dead stay around as ghosts. When the first human dies and returns as a spirit, the chaplain seeks help from an alien priest to help the man move on.

It's a great premise, but the story doesn't quite deliver. In fact, it doesn't do much at all. The chaplain and the dead guy walk to the planetary pole. He passes without incident. Then someone else dies. The chaplain thinks the humans can handle it this time. THE END.

My writing is often criticised for lacking 'jeopardy'. You know, those knotty fictional situations that have you clutching the bedclothes and squirming at the protagonist's predicament. Is Indiana Smith scared of snakes? Well, the only way he can save his daughter is by crossing the snake pit of doom.

On A Spiritual Plain has zero jeopardy. The guy dies. He seems cool with that. The chaplain asks the aliens for advice. They're delighted to help. They all walk to the pole. The dead guy makes peace with his situation and passes on smoothly. Some other person dies. The chaplain is cool with that too. There's not one hint of conflict or ethical dilemma. No one is forced, by desperate circumstances, to challenge the beliefs they hold dear and undergo meaningful, lasting change.

It's notable that my copy of the short story has a 'Food for Thought' section at the back, which explains the ethical issues raised. It's akin to modern art exhibitions that have a splatter of red paint on a white background, and a twenty-page explanation of what that means. If your story doesn't convey the ethical dilemma, without further explanation, perhaps you should rewrite it.

I should say something positive, so I will. On A Spiritual Plain is clearly written and easy to read. Not all the Hugo Award short fiction nominees manage that feat, so it's worth a mention.

#3 A Single Samurai by Steven Diamond

A Single Samurai is on the border of 'No Award' and 'Ok, I'll vote for this story to stop it looking like I'm making an anti-Puppy protest'. It's not a profound story, it's not breaking new ground in science fiction, but it is well-written and effective. The author had evidently done some research into samurai and it shows, e.g. the wakizashi sword.

It's also among the best stories with a single character I've ever read. It tells the tale of about a lone samurai who sacrifices his life to protect his country from a monster the size of a mountain. He is inspired in this feat by the example of his father, who sacrifices his own life to protect the honour of his lord. I felt the ideas of honour, life in a feudal society and personal sacrifice were well-explored.

'In front of our local magistrate, my father shrugged off the top of his robe and let it fall to the ground. He slipped his wakzashi from the scabbard, reversed his grip on the blade, and settled the point against his flesh.

I glanced at the magistrate and saw the sadness that filled his eyes.

My father had not been the one to cause offense. My father's lord had been the one to do that. But even with his faults, our lord was the best person to lead. The best person to see our people through different times. My father knew that.

So he offered to cleanse his lord's honour with his own life.

The trouble is A Single Samurai is just a monster story. It doesn't do anything that the Epic of Gilgamesh didn't do, and that was about 4,000 years ago. It's not 'kaiju for the 21st century'. It's not 'kaiju invade contemporary Manhattan' or 'kaiju attack reality TV stars'. It's about a lifestyle, honour code and era that is long past.

For me, a Hugo Award winner has to be a product of its time... And that's a shame because I'd love to vote A Single Samurai for 'Best Pulp Monster Story of 2015', an award it heartily deserves because it is very cool.

#2 No Award - self-explanatory

#1 Turncoat by Steve Rzasa

I didn't expect to like Turncoat. I don't read military SF and I was somewhat daunted by the beginning of the story, which appears to kick off with a tech-dork-porngasm of military equipment. I expected a Republican senator straddling a phallic-shaped missile by page five.

My suit of armour is a single Mark III frigate, a body of polysteel three hundred meters long with a skin of ceramic armour plating one point six meters thick. In place of a lance, I have 160 Long Arm high-acceleration deep space torpedoes with fission warheads.

In fact, the story evolved into the sweet tale of a AI's love for its irritating, but oddly companionable, human crew. And its sadness and loneliness when they are dismissed, which leads it - inexorably - to defect and seek asylum with humanity.

Stories of machine intelligences deciding that humans are obsolete are ten-a-penny, but what was new (to me) in this story was the idea that humans can be likable. Not useful. Not better than an AI, but enjoyable companions in the dark void of space. It made me think of what I call the absent dog problem. That feeling when you walk into your house and the sofa is empty, and there's no one there to greet you with a bark and a wagging tail.

The writing is overly technical and impenetrable, but I didn't mind that. I'm a 'voice writer'. And the narrator of Turncoat definitely has the right voice for a military machine intelligence. Very technical. Very numerical. Very precise. The story wouldn't work if the narrator sounded like Rebecca Bloomwood.

When we depart 540 kiloseconds later, my frigate is faster, stronger and quieter. Inserting myself into the command matrix is euphoric. Connections between my various systems are instantaneous. Oceans of data flood my senses. I can see everything. I can do anything.

And yet it is too quiet. There is no inane chatter from my crew. No rhythm of their boots on deck plates. No soft hum of air through the ventilation shafts. No scent of an overworked crewman or a stressed officer wafts through my corridors.

Turncoat isn't the greatest story I've read, but it's definitely the best out of a bad bunch. And a total surprise - I never expected to like this one.

What I think counts as good short SF&F fiction

Paolo Bacigalupi's The People of Sand and Slag

Robert Sheckley's A Wind is Rising (not Hugo quality, in my opinion, but a nicely-structured joke)

William Gibson's Johnny Pneumonic

Outside of SF&F, They're Not Your Husband by Raymond Carver is a masterpiece. It communicates a subtle, profound truth about the human condition with an economy of words.

And finally, I don't criticise without exposing myself to criticism. Berlin Sting is one of my early shorts (2,000 words). I've never tried to get it published. Wouldn't know where and I don't have the confidence.

Five Guides for Puzzled Writers

Given the choice between reading a book about doing something... or doing that thing, I opt for the book every time. Which explains why I must have opened every 'How to Write Fiction' book ever written. Opened... Read a couple of pages. And - in most cases - put back down again.

I don't have the world's longest attention span, and you've got to be short, funny and/or include pictures to keep me reading. Surprisingly, that isn't an impossibly hard task.

1. How Not to Write a Novel

Write better... or the kitty gets it...

This has be a brilliant book. JUST LOOK AT THE COVER. On a more serious note, How Not to Write a Novel does exactly what it says on the tin. It uses made-up examples of excruciatingly bad writing to illustrate how not to tackle plot, character, dialogue, setting and voice. It's snarky, it's very rude, I laughed out loud in places... and I wished I'd written it myself.

Pick up this book today and, if you've been writing for a while, I challenge you to read it without cringing at least once. Authors' website is here.

Quote from How Not to Write a Novel, page 55-56:

Some descriptions of characters sound like a police report:

Joe was a medium-sized man with brown hair and brown eyes.

Alan wore a white shirt and blue jeans on his tall frame.

Melinda had a nice body and a pretty face.

Descriptions like this make your characters feel like stick figures. No one thinks of himself as a brown-haired man of average height. Police-report descriptions in general will be received by the reader much as if it had read "Horace was a man with two legs, two arms, and a head on top." [...] If you're going to tell us something about a character, tell us something that we wouldn't have assumed on the basis of species and gender. Err on the side of specificity. Novels are seldom rejected because the characters are described too well. Try to concentrate on features and qualities that are specific to your character, or if your character is in fact average, describe those features in a way that is specific to your character, a way that suggests her personality. ("Marianne detested the way she didn't stand out in a crowd.")

2. The Story Book

Storytelling is among the oldest human traditions, so you may wonder why you need a book on 'How to Tell a Story', but telling a story in two, five, or 150,000 words is harder than it looks. There's a reason why William Shakespeare is still showing in British theatres after 450 years. He created plays that tickled the human desire for stories with conflict, rising tension and a clear beginning, middle and an end.

Story by screenwriting guru Robert McKee is The Definitive Textbook for storytellers, but I prefer The Story Book. It is a step-by-step guide to story creation that turns novels into flat-packed furniture with words. Still annoying and fiddly to put together, but at least you've got a screwdriver and a plan. It covers the same ground as Story, but it's shorter and less academic... And it has pictures. Click here to visit the author's website.

Pictures from The Story Book, page 90-91:

I used Story Book to plan my own work-in-progress novel (in an Excel spreadsheet...). Wrongly or rightly though, my book sometimes sacrifices story for milieu, which brings me neatly onto my third entry...

3. A Writer's Digest Guide to Science Fiction & Fantasy

This guide by Orson Scott Card first introduced me to MICE. No, not squeaky cheese eaters. MICE is short for Milieu, Idea, Character, and Event.

A story is how we humans make Events entertaining. We tell tales by saving the most exciting event until last. Did Fred slay the dragon? Did Helena get the guy in the end? The Story Book tells you how to sequence Events, but only high-octane thrillers are 90% event.

In science fiction, fantasy and historical fiction, the setting - Milieu - is as important as what happened. A murder in Tudor England and on Mars aren't the same story. Likewise, science fiction was traditionally a novel of Ideas, asking ethical questions like whether smart robots should have the same rights as people. Finally, literary fiction often focuses on the psychology or inner turmoil of Characters.

Since novels have word limits, Milieu, Idea, Character and Event compete for space in your story. Showing Martian cuisine reduces the amount of words you can spend developing Freda's relationship with her aunt. There are a lot of assumptions embedded in a high-octane made-up-by me-on-the-spot first line like:

'The President of the United States dived behind the desk, but I had already aimed the Glock and pulled the trigger'.

We're on present-day Earth, maybe in the Oval Office, the President is being assassinated, and this will probably set in motion a major international incident - maybe even nuclear war. The weirder your setting, the harder it is to produce an Event-driven first line like that one. There's a reason why SF&F writers often use tropes like vampires, zombies and cyberpunk megacorps...

Quote from The Writer's Digest Guide, page 77:

The milieu is the world - the planet, the society, the weather, the family; all the elements that came up during the world creation process. Every story has a milieu, but in some stories the milieu is the thing the storyteller cares about most. For instance, in Gulliver's Travels, Swift cared little about whether we came to care about Gulliver as a character. The whole point of the story was for the audience to see all the strange lands where Gulliver travelled and then compare the societies he found there with the society of England in Swift's own day - and the societies of all the tale's readers, in all times and places.

The MICE Quotient isn't the only reason to pick up this ring binder, but that's worth the entry price alone - especially if you're writing SF&F. Visit the Writer's Digest website here.

4. How to Write the Perfect Novel: A tongue-in-cheek guide to certain literary success

I did not know the dog's name. He stared at me from the rusted, rotten twisting metal and concrete of a decayed groyne. I stared back.

'Genre' is one of those strange terms you'll hear as a beginner writer. What 'genre' is your book in? A Death at the Vicarage is in the mystery 'genre'.

How to Write the Perfect Novel is the best guide to genre you're ever going to read. And it uses the time-honoured tradition of making stuff up and taking the mickey. If you've ever wanted to read mick-takes of the worst romance, literary, spy or crime writing - now you can.

Quote from How to Write the Perfect Novel (literary fiction), page 47:

"Dog," I said.

He cocked his head yes

"Why don't you have any punctuation?"

Dog laughed Haven't you figured it out yet

I shook my head. "Why do you sit here, dog, day after day?"

Dog smiled I'm a literary cipher mate It's my place to be enigmatic and make readers wonder what my symbolism is I'm a bleedin metaphor

"For what?"

That's for me to know and you to find out moosh probably on page 362 when the book finally ends but in such a wet indefinite way that the reader will be left scratching his noodle wondering what the fuck all that was about If he makes it that far

5. On Writing

Stephen King is among the world's most best-selling authors. According to Wikipedia, his books have sold more than 350 million copies.

On Writing is a combination memoir and textbook for writers. King rambles a bit (as he does in his books), but this is the airport novel of writer's guides. King is a genius storyteller. It's a warm, easy read and you learn something at the end. Bonus. You can visit his website here.

Quote (shortened) from 'What Writing is' from On Writing, pages 113-117:

All the arts depend on telepathy to some degree, but I believe writing offers the purest distillation [...]

Look - here's a table covered with a red cloth. On it is a cage about the size of a small fish aquarium. In the case is a white rabbit with a pink nose and pink-rimmed eyes. In its front paws is a carrot-stub upon which it is contentedly munching. On its back, clearly marked in blue ink, is the numeral 8.

Do we see the same thing? We'd have to get together and compare notes to make absolutely sure, but I think we do. There will be necessary variations, of course; some receivers will see a cloth which is turkey red: some receivers will see one that's scarlet, while others may see other shades. Decorative souls may add a little lace, and welcome - my tablecloth is your tablecloth, knock yourself out.

[But...] We all see it. I didn't tell you. You didn't ask me. I never opened my mouth and you never opened yours. We're not even in the same room... except we are together.

We're close.

We're having a meeting of the minds.

Sad Puppies: Some Numbers

Nathaniel Givens at Difficult Run has done some fascinating data analysis on the 2015 Hugo Awards/Sad Puppies controversy. Among other things, he writes:

Back in 2013 a Tor UK editor actually divulged the gender breakdown of the submissions they receive by genre.

So, over the history of the Hugo awards from 1960 – 2015, 79% of the nominees have been male. In 2013, 78% of the folks submitting sci-fi to Tor UK were male.

And:

If you have a situation where men and women are equally talented writers and where men outnumber women 4 to 1 and where the Hugo awards do a good job of reflecting talent, then 80% of the awards going to men is not evidence that the awards are biased or oppressive. It is evidence that they are fair. In that scenario, 80% male nominees is not an outrage. It’s the expected outcome.

I read the Tor UK article and drew the same conclusions. The data analysis is definitely worth a read.

Image labelled for reuse: https://c1.staticflickr.com/1/7/11314489_a7c52be257_b.jpg

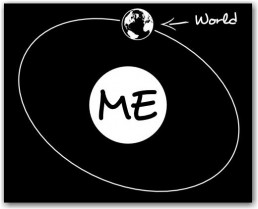

I am reality, hear me roar...

During my MFA in creative writing, I had a few critique sessions with a Costa-Award-winning novelist. I learned a lot from him since, unlike most lecturers, who nodded sagely while the class gave feedback, he talked while we shut up. He was a successful literary writer, we weren't, and learning from him was what I was paying for.

I remember one short story he critiqued. The first lines contained something like:

The sea beyond the window was unimaginably huge.

He told the author that "unimaginably huge" was a character's opinion, not external reality, and fact and opinion should be clearly separated in fiction. He suggested something like:

The sea stretched out towards the horizon, glittering under the moon. He thought how unimaginably huge it was.

His argument was stories can feel claustrophobic when external reality is filtered though a character's point-of-view. Even everyday objects, such as chairs, become matters of opinion - and the overall reading experience is like being trapped with a loud-mouthed jerk in a lift. By separating physical reality from opinion, the reader can stand beside the character (gazing at the sea) rather than being crammed inside their head like an alien bodysnatcher.

The Puppygate controversy dogging this year's Hugo Awards for SF&F got me thinking about that MFA class. Yesterday Hugo finalist Annie Bellet withdrew her nomination for "Goodnight Stars" , which was on the Sad Puppy slate. Her short story was replaced (I think) by Thomas Olde Heuvelt's "The Day the World Turned Upside Down", which - of course - some Puppy supporters think is dreck.

I've read both stories, last year's Hugo winner "The Water That Falls on You from Nowhere" and the now-infamous short "If You Were a Dinosaur, My Love". They're all well-written, but "Goodnight Stars" and the non-Puppy-supported stories differ in one important respect. And that's their approach to external reality.

"Goodnight Stars" is about a woman called Lucy trying to return home from a camping trip, after the moon explodes and showers Earth with meteors. Lucy's mother was on the moon, and her driving force is to discover if her mum is alive. The story feels *real* and moving because the moon is an external reality independent of Lucy's emotional state.

"The Day the World Turned Upside Down" is also a disaster story in which the narrator tries to get back together with his girlfriend by rescuing her goldfish after gravity is reversed, causing people to fall off the Earth. The girlfriend rejects him, he can't let go of her, and the story ends with him climbing down a rope ladder dangling into the void... Not letting go.

Here's my problem with "The Day the World Turned Upside Down" (and the fantastical elements in "The Water That Falls..."). Not only does the reader lack access to external reality. There *is* no external reality.

Say you're a soccer player who flunks a game. You're still moaning that night in a pizzeria, and your teammate says "Stop crying over spilt milk, dammit!" Back at home, your fridge explodes, flooding the floor with semi-skimmed, and the next morning a passing milk truck crashes through your front wall.

You might start wondering whether you're a fictional character, stuck in a gigantic metaphor for "getting over a past loss", and with the power to unconsciously shape the stuff of reality into a reflection of your angst. The milk truck driver? Who cares about his feelings; the world revolves around you.

It's obvious why the Puppies call these type of stories "message fiction", especially when they're political. Unlike in literary fiction where only characters carry the message, in SF&F the fabric of the universe can do so too. The loud-mouthed jerk *is* the lift.

Now *that's* claustrophobic...

CORRECTION: "The Day the World Turned Upside Down" did not replace "Goodnight Stars", but instead replaced the novelette "Yes, Virginia, There is a Santa Claus" by John C. Wright (hat tip to John C. Wright for the correction - see comments)

Image source: http://ccdumaguete.com/new/2011/06/25/the-heart-of-the-matter-the-who-of-worship/ Labelled for reuse.